To Tommy

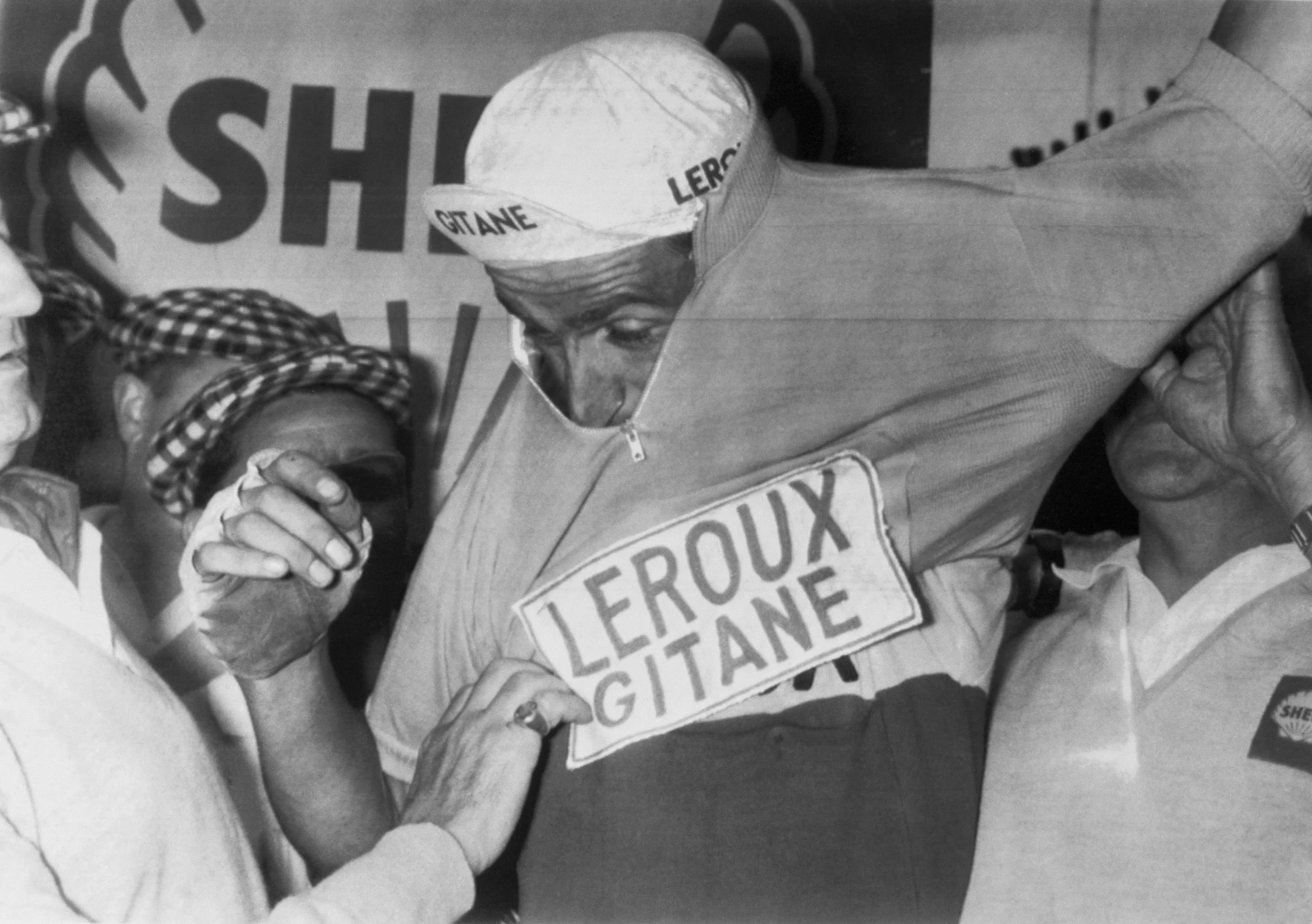

An infamous death, a career as one of Britain’s greatest ever road racers, and a personality to match his talent, Paul Simpson writes about the life – and passing - of cyclist, Tom Simpson.

When Pierre Dumas, the official doctor of the Tour de France, smelled the heat outside his hotel in Marseille early on the morning of July 13 1967, he confided to journalist Pierre Chany: “If the boys stick their nose in a ‘topette’ [bag of drugs] we could have a death on our hands today.” In his hotel, Tom Simpson, the greatest cyclist Britain had produced until that time, must have sensed the heat too as, beset by diarrhoea and stomach pains, he steeled himself for the thirteenth stage of the Tour, a gruelling 211km (131 mile) route from the Mediterranean port to Carpentras via the region’s highest mountain Ventoux (the name essentially means windy), a 1,909m (6,263ft) high peak known locally as the Giant of Provence.

At 29, Simpson was already contemplating his next career, envisaging a lucrative round of personal appearances – but even so, he must have been perturbed by his personal manager Daniel Dousset’s warning, issued only the night before, that if he didn’t do well on this Tour, he might as well give up cycling. A large contract from an Italian company hung in the balance.

At the starting line-up in Marseille, Simpson looked so ill that a reporter asked him if the heat was troubling him. The cyclist replied: “No, it’s not the heat, it’s the Tour.” Later that same afternoon, Dumas’s prediction came tragically true when Simpson collapsed and died on the climb to Ventoux. The Tour’s doctor had to order a police helicopter to carry the dying racer to hospital in Avignon. The official cause of death was “heart failure caused by heat exhaustion” – the temperature that afternoon had soared to 49C – but the autopsy concluded that amphetamines, alcohol and a stomach virus had played their part too.

Simpson was the first rider to die on the Tour de France since 1935 – when Spanish racer Francisco Cepeda plunged down a ravine – and the tragedy quickly became known as the sport’s equivalent of the JFK assassination, a moment in time where everyone could recall where they heard the sensational news. The footage of his final moments – though not as viscerally shocking as Zapruder’s film of JFK’s murder – is still hard to watch, especially the moment when his bike starts to wobble as if he were a novice, crashes and, then, a few seconds later, at his mumbled insistence, is remounted. His often-quoted final words “Put me back on my bike” were invented by Sun journalist Sid Saltmarsh. In some ways, his actual last words - “On, on, on” – are even more poignant because they capture the ethos that made him so great. The best way to understand Simpson’s impact on British cycling is to cite John Lennon’s star-struck remark to Elvis Presley: “Before you there was nothing.”

As with Kennedy, there is a danger that Simpson’s life becomes a footnote to his iconic death. Indeed, only the day after his death in Provence, that shift in perspective had already begun. The Guardian’s Geoffrey Nicholson reported, rather patronisingly, that: “As a rider, he was only just short of the very highest class.”

Among those who have subsequently disagreed with Nicholson are Sir Bradley Wiggins who wrote, in his book Icons: “Simpson is arguably the most complete British road cyclist of all-time. Mark Cavendish was a better sprinter, I was a much better time triallist and Tom couldn’t climb like Robert Millar. However, none of us could have won so many big important races and widely diverse races and it is very unlikely that anyone from these shores ever will.” The authoritative Road Cycling UK ranks Simpson as the seventh best British road cyclist of all-time, two behind Sir Bradley.

It wasn’t just what Simpson won, for Wiggins, it was how he won: “Professional athletes are quite insecure anyway and as often it’s the small things that make the difference. Tom’s smile helped me no end.” That was one of many reasons why the five-time Olympic gold medalist had a photograph of Simpson taped to his bike when he rode past Ventoux on the 2009 Tour.

Simpson never won the Tour de France but in 1962 he came sixth, the best finish by a cyclist from these shores, making him the first – of eight – British cyclists to wear the coveted yellow jersey as a stage leader. The other seven, in chronological order, are Chris Boardman (who wore it three times); Sean Yates; David Millar; Wiggins; Chris Froome (four times); Mark Cavendish; Geraint Thomas (twice) and Adam Yates.

Three years after his landmark achievement in France, Simpson became the first British rider to win the Italian classic Giro di Lombardia – he remains the only one to do so – and the world road racing championships. In the closing stages of the latter, when he was neck-and-neck with German cyclist Rudi Altig, an old friend and rival, he pretended to be weaker than he really was. In the sprint finish, he launched a surprise attack, just as Altig fluffed a gear change, and seized the crown.

Such historic exploits – and his image as a swashbuckling, upwardly mobile sporting hero, capturing the zeitgeist of Britain’s Swinging Sixties – earned him the accolade of BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

It is hard now, accustomed as we are to the exploits of Wiggins, Cavendish, Boardman and Froome, to understand just how unlikely Simpson’s success was in the late 1950s and 1960s. To put things in perspective, Luxembourg won the Tour in 1958, 54 years before Britain – and Wiggins - did in 2012. At the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Britain’s cyclists didn’t win one measly medal.

Born on November 30 1937, in Haswell, County Durham the youngest of six children in a mining family, Simpson grew up in Harworth, a Nottinghamshire pit village, and didn’t ride a bike until he was 12, sharing it with his brother-in-law and some cousins. At the time, cycling was a minority sport in Britain, plagued by an ongoing civil war between two governing bodies. At his first cycling club, he was quickly dubbed ‘four-stone Coppi’ after the Italian legend Fausto Coppi, a nickname that acknowledged his slight build while, quite possibly, alluding to his penchant for blowing his own trumpet.

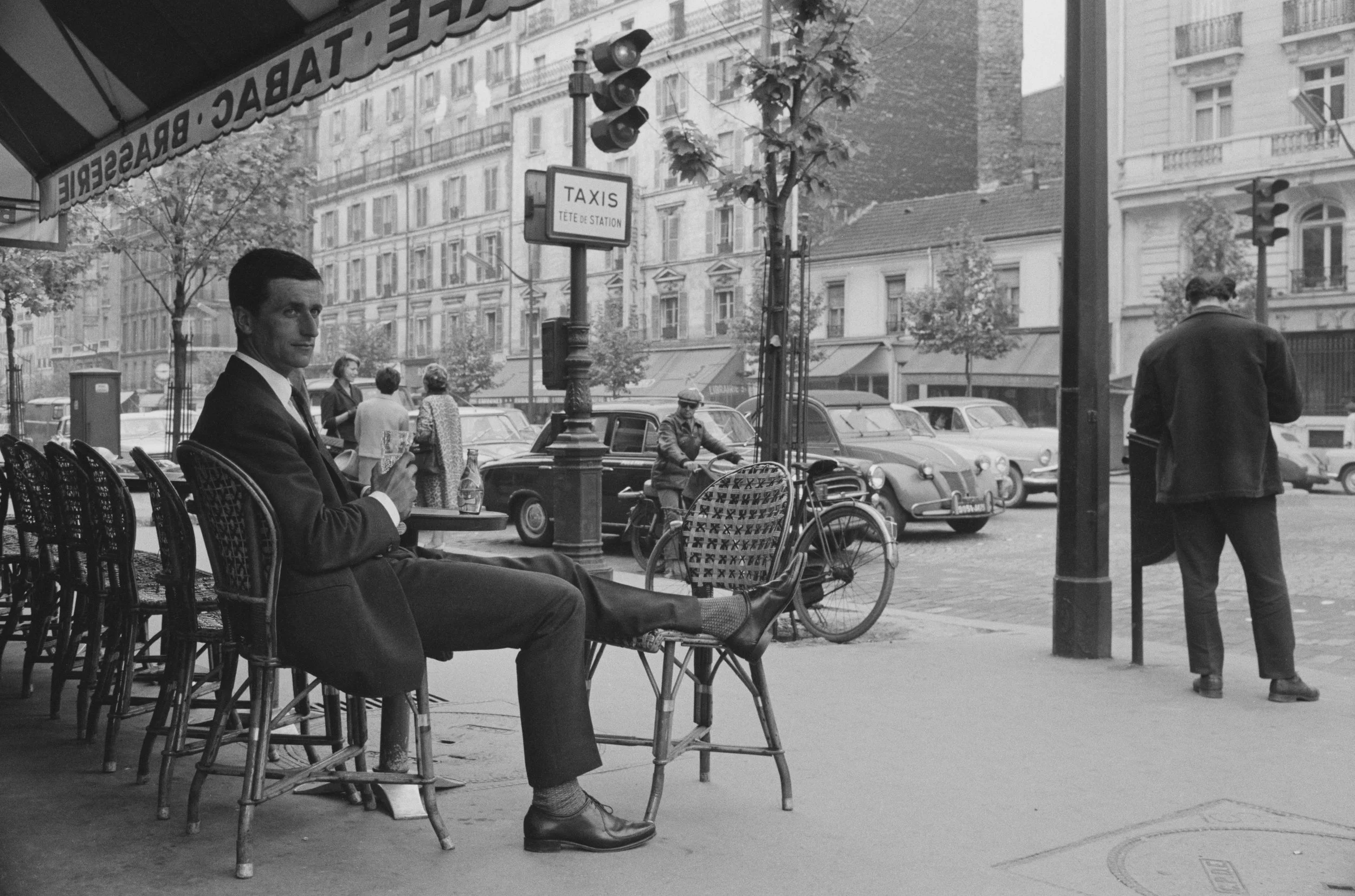

Although Simpson won a bronze medal with Great Britain’s pursuit team at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, he became convinced he had to move abroad to reach the top. As he told his mother in April 1959: “I don’t want to sit here in 20 years, wondering what would have happened if I’d gone to France.”

He left for Brittany with £100 in cash, a car, and two bikes and quickly made a name for himself. Brian Robinson, one of the first British riders to finish the Tour de France (in 1955) recalled: “I first became aware of Tom in 1959 when I heard about this British lad who was winning loads of races in Brittany. He came to visit us on the Tour that year and I introduced him to the manager. They agreed he’d sign for the St Raphael team there and then and on better money than I was on.”

Money – and the need for it – is an often overlooked influence on Simpson’s life and untimely death. Branding himself as the quintessential British gent, sporting a bowler hat in photo shoots, went down well in continental Europe, even if the image was a tad misleading: as a miner’s son, he wasn’t exactly to the manor born and, speaking several languages and adopting Ghent as his second home, was more cosmopolitan than this persona suggested. Indeed, in a photograph widely published in France to mark his death, he is pictured reading Les Carnets du Major Thompson, a witty novel about a retired British officer’s impressions of French life, by Pierre Daninos. This was not just PR. As after a year abroad, he gave all his post-race interviews in French.

Having played up to his nicknames ‘Major Tom’ and ‘Major Simpson’, he became, in 1966, the first cyclist to appear on Desert Island Discs where, in an artful performance, he selected Ari’s theme from the 1960 blockbuster Exodus as his favourite track, Charles Dickens’, as his book and golfing equipment as his luxury item.

Simpson was completely candid about why he sought the spotlight, saying once that it was an athlete’s job, “To secure as much publicity as possible for his sponsors. He is an entertainer, a publicity agent and a sportsman all rolled into one, in that order.” Whether his sponsors made fridges or washing machines, he added, they wanted their investment to boost sales. Simpson charmed the French media by donning different headgear – sombreros, firemen’s helmets and flat caps – at different events, driving around Paris in an open-topped car with a rolled-up umbrella and once brandishing a ukulele in a half-decent impersonation of George Formby.

The rules of sporting celebrity were still being written when Simpson rose to fame – George Best, ‘El Beatle’, was still two years away from emerging as British football’s first rock star – and in 1963, he made a rare error of judgement, spilling some trade secrets to the People newspaper. In the interview, he talked about paying another rider to help him, taking money to help a competitor and using ‘medical tonics’. He was nearly fired from the Peugeot team (which he had only recently joined), was subsequently approached by – and had a minor scuffle with – his idol Jacques Anquetil (the first man to win the Tour five times) and outraged the British Cycling Association.

Simpson burnished his legend with his erratic, extrovert, behaviour, even while competing in a race. In 1967, when he was the undisputed leader of the Great Britain team on the Tour, he whipped off team-mate Colin Lewis’s hat at one stop. “What do you want that for Tom?” asked Lewis, who was riding in his first Tour. “I need a shit,” Simpson replied, “And I need to wipe my arse on it. Wait for me.” This was no one-off: when Andy McGrath researched his biography Bird On The Wire, almost every rider he interviewed had an anecdote about Major Tom’s eccentricities.

Simpson knew that to maintain his high profile – and support his wife Helen and two daughters, Jane and Joanne – he had to win races. Wondering what drove him to his death, David Saunders, who collaborated on the rider’s autobiography Cycling Is My Life, wrote: “Ambition? Vanity? Money? Certainly not vanity. Ambition could have been his downfall. Perhaps, though, it was the money. He had a burning desire to make enough money so he could retire early and enjoy life with his wife and two daughters.”

Simpson won his first classic event, the Tour de Flanders, in 1961 before riding to glory in the Bordeaux-Paris race in 1963 and the Milan-San Remo in 1964. Between 1964 and 1966, his campaigns in the Tour were successively disrupted by a tapeworm, a septic hand which nearly had to be amputated, a broken leg (caused by a skiing accident) and two bad crashes. This cavalcade of calamities was partly due to sheer bad luck but also reflected his aggressive, attacking riding style.

Simpson was a maverick but a grimly determined one. He once pursued and passed British rider Barry Hoban in a race, even though he didn’t need the points. Asked why he’d bothered, he told Hoban: “Because I’m the number one British rider. Not you.” He could, according to his nephew Chris Sidwell, be flippant with people he didn’t like or rate but he was also sincere in his adoration for Coppi and Aquentil, the reigning gods of cycling in that era, and thrilled that, somehow, he had come to compete alongside them.

His first classic victory, the 1961 Tour de Flanders, was a tactical masterclass. As one of his biographers William Fotheringham recalled, Simpson outwitted the vastly more experienced (and faster) Italian rider Nino Deflippis: “[He] pretended to sprint to the finish and stuck his tongue out to convince his rival that his legs were fading. Once the Italian had made his effort and overtaken him, he attacked on his blind side to win by inches.” Earlier in the race, he had kidded Defilippis by assuring him that he didn’t need to amass too great a lead because, “You can get ten metres on me in the sprint.”

One of Simpson’s contemporaries, Jean Stablinsky described him as “the complete rider, combative, but also sly and cunning. You wouldn’t notice it, but he knew how to trick you in a race, how to get the breaks – the right breaks”. Another French rider, Jean Bobet likened him to a bird of prey, blessed with a complete understanding of his surroundings and an innate instinct for choosing the perfect moment to spread his wings.

Before the 1967 Tour, the stakes were higher than ever for Simpson who had put down a deposit on a top-of-the-range Mercedes, confident that he could pay off the balance with his winnings and subsequent earnings from endorsements and public appearances. His determination to become the first Briton to win cycling’s greatest race was almost certainly reinforced by the sense that he wouldn’t have that many more chances to make history.

His confidence would have been buoyed by his victory in the Paris to Nice race in March. As Peugeot’s team leader, Simpson was dismayed that, with five days to go, his younger colleague Eddy Merckx was ahead of him. On stage four, he caught up with a 14-rider break – an attack designed to raise the pace – and finished third. The Belgian rider was so incensed he refused to speak to Simpson and told journalists he had been double-crossed. The riders made it up and later, Merckx was generous enough to admit his debt to his team leader, saying he had been ridiculed at Solo Superia, his first team, and learned how to win – and to celebrate – from Simpson, saying: “He was a very good rider. He really put me in my place after I thought I was on my way to winning it.” As the Belgian went on to win five Tour de Frances, five Giros Italias and one Vuelta a Espania, that was high praise indeed.

Yet biographer McGrath has suggested that the Tour’s allure might have led Simpson astray: “He is underrated as Britain’s greatest one-day racer and overrated for his achievements on the Tour. I came to realise that the Tour was the race he wanted the most that probably suited him – and his exciting riding style – the least.”

To spectators, whether they are watching on screen or in person in one of the many towns and villages the race winds through, the Tour looks like a glamorous adventure, as picturesque and colourful as a carnival. That is not how it feels to the riders who, if they complete the race, will have ridden more than 3,500km (2,170 miles) over 21 days, a distance roughly comparable to the famous Oregon Trail wagon route from the Missouri river to the Pacific state. (The route was even longer in Simpson’s day.) Lucien Aimar, the 1966 champion, once explained why the race was so exacting: “It’s where all of your faults and weaknesses come out.”

In the Tour’s sprint stages, Australian academic Chris Abbiss has estimated that, to overcome wind resistance and reach a competitive speed of around 80km/h (50 mph), cyclists must generate at least 2,000 watts of energy - enough, he says, ‘to power a fridge, TV and most of the lights in an average house’.

On the mountain climbs, often crucial to the race’s outcome, the high altitudes make it so hard for oxygen to reach the muscles that, Abbiss estimates, a rider’s capacity to exercise can be reduced by 10-15 per cent. Many experts believe that the climb to Ventoux is not even the Tour’s most gruelling mountain stage, with Col de la Loze, in the Alps, and Col de Portet, the highest mountain pass in the Pyrenees, reckoned to be tougher still.

No Tour de France champion wins every stage of the race. Indeed, only three riders – Merckx (1974), Bernard Hinault (1979) and Wout van Aen (2021) – have won all three specialties, mountain, sprints and time trials, on the same Tour. One of the stages Simpson had identified as critical to his race was that between Marseille and Carpentras. On the night of July 12 1967, his mechanic Harry Hall jotted down in his notebook which gears he had fitted for the route: “Ventoux: 14, 15, 17, 19, 22, 23. Rest OK.”

Nobody can say for sure how many drugs Simpson took before – or during – his last ride to Ventoux. We know he took amphetamines because two empty tubes were found in his back pocket. We know, too, that he topped up his water bottle with brandy but again we’re not sure by how much. (This was an era when so little was known about the effect of long distance riding on the human body that team managers routinely gave cyclists whisky and brandy to perk them up.)

The Simpson family never saw the autopsy report which, as is usual practice in France, was destroyed after 30 years. His youngest daughter Joanne remains dissatisfied with the media’s reductive verdict that he doped himself to death. On July 31 1967, Daily Mail sportswriter JL Manning made the sensational claim that Simpson “rode to his death … so doped up that he did not know he had reached the limit of his endurance. He died in the saddle slowly asphyxiated by intense effort in a heatwave after taking amphetamine drugs and alcohol forbidden under French law.”

In 1965, partly at the behest of the Tour’s official doctor Dumas, France had passed its first anti-doping law for cycling. The initial tests, in 1966, revealed that one in three riders had taken amphetamines. In reality, as Alec Taylor, Great Britain’s team manager in 1967, remarked later, drug abuse was much more prevalent: “I saw on the continent the over-cautious way riders were tested for dope, it was as if the authorities feared to lift the veil, scared of the results, knowing all the while what they would be.”

There was a sense of corporate complicity among riders, who felt they had calculated the risks, deemed them worth taking and assumed that they would not face the consequences, protecting each other with a veritable pact of omerta. Resenting the first tests, even if they were desultory, some racers on the 1966 Tour had shouted at Dumas, demanding he be tested for wine and aspirin which they claimed he was using to handle the stress.

It is hard, now, to understand such a mindset but French rider Jean-Marie Leblanc, who would later serve as director of the Tour, recalled later that “Simpson had too much pride but in the good sense. He wanted to do too much, had too much self-esteem. But that is one of the elements that makes a great champion, that they could drive themselves right to the end.” That view was echoed by Simpson’s friend and fellow rider Robinson who said: “He had the ability to win without the drugs, that’s the sad bit. But once one starts, another says ‘I’ll take this’ because I need to beat him. Tom’s fault was that he had to win.” Simpson once joked about his risk-taking, writing: “If ten will kill me, I’ll take nine and win.”

Even so, the dangers of such pride were becoming dramatically apparent. On the 1960 Tour, France’s Roger Riviere rode so fast down a mountain that he overshot a bend and fell into a ravine, breaking his back. He blamed faulty brakes, but tests revealed that he had so much opioid painkiller in his system that his hands were too slow to work the levers. He subsequently admitted taking thousands of tablets a year in his determination to break cycling records. Later that same summer, Danish cyclist Knud Enemark Jensen collapsed in 40-degree heat in Rome, during the 100m Olympic time-trial, and died without regaining consciousness. Officially, the cause of death was heatstroke but one doctor who conducted the autopsy found traces of amphetamines.

“Streaming with sweat, haggard and comatose, he was zig-zagging and the road wasn’t wide enough, he was no longer in the real world, even less in the world of cycling and the Tour de France.”

Tragedy in Rome was followed, two years later, by tragicomedy on the 1962 Tour when 20 riders fell ill en route to Carcassonne and 11 abandoned the race. Every racer blamed a dodgy fish meal the night before – even though none of the hotels in Luchon, where they had stayed, had fish on the menu.

The incident which makes Simpson’s tragedy feel like a chronicle of a death foretold took place on the 1955 Tour when, on the climb up Ventoux, French rider Jean Mallejac was, as one journalist put it, “streaming with sweat, haggard and comatose, he was zig-zagging and the road wasn’t wide enough, he was no longer in the real world, even less in the world of cycling and the Tour de France.” He collapsed to the ground, completely unconscious, his face as pale as a corpse, with freezing sweat running down his forehead.

Quickly summoned, Dumas had to physically force Mallejac’s jaws open to give him a drink. It took 15 minutes, a dose of camphor and blasts of oxygen before the rider came around. He still didn’t grasp how desperately ill he had been. As he was bundled into the ambulance, he started gesticulating, shouting to be let out and demanding his bike back.

In hospital in Avignon - where Simpson would be pronounced dead on arrival seven years later – Mallejac protested that he had been given a drugged water bottle by a soigneur (as rider’s assistants on the Tour are called). He refused to name names, even though Dumas said he would press for a charge of attempted murder. The mystery was never resolved.

The heat, the zig-zagging, the drugs and above all the setting – known to locals as the ‘sorcerer’s cauldron’ – make Mallejac’s brush with death feel like a minor prequel to that fatal accident on July 13 1967.

“The Giant of Provence is a great mountain stuck in the middle of nowhere and bleached white by the sun,” is how Simpson described Ventoux in his autobiography, after riding up and down it in 1965. “It is another world up there among the bare rocks and the glaring sun. The white rocks reflect the heat and the dust rises, clinging to your arms, legs and face.” Lewis made the same point more succinctly describing the climb as “hell on wheels”.

French novelist Antoine Blondin believed there was something sinister about the mountain, noting: “We have seen riders reduced to madness under the effect of the heat or stimulants, some coming back down the hairpins they thought they were climbing, others brandishing their pumps and accusing us of murder … Falling men, tongues hanging out, selling their soul for a drop of water, a little shade.” Philosopher Roland Barthes went so far as to call Ventoux ‘an evil god to whom sacrifices must be made’.

At 1909m (6,263ft) high, Ventoux is the highest peak in Provence. The average gradient on the climb is around 7.4 per cent but there is a 5km (just above 3m) stretch where that rises to around 10 per cent and a 500m (1,800 yard) segment where it reaches 11.6 per cent. American medic Gabe Mirkin has explained, in graphic detail, what Simpson would have, hopefully unknowingly, endured: “The most common cause of death during hot weather sports is heatstroke in which the body temperature rises so high it cooks the brain like an egg in a frying pan. Amphetamines can increase the risk of heatstroke by preventing your brain from recognising the signals.” And many of those symptoms – feeling like the air you breathe is coming from a furnace, blurred vision, ringing in the ears and severe shortness of breath – only become apparent to the victim when it is already too late.

His fastidious biographer Fotheringham concluded that heatstroke was the principal cause of Simpson’s death, although aided and aggravated by amphetamines, alcohol and a stomach virus. The bug was so severe that, only two days before, his mechanic Hall had wiped the evidence of diarrhoea off Simpson’s bike at the end of a stage. In other words, one of the greatest British cyclists of all time should never have been racing that day in the first place.

On the ascent, Simpson drank more than usual. Opinions differ as to whether there was brandy or only water in his bottle. His GB team-mate Lewis remembered stopping off at a village cafe to buy some Cokes. In the rush, he bought a brandy and, realising his mistake, was about to discard it when Simpson said: "No, give us that, my guts is a bit queer.” According to Lewis, he threw the bottle away after one swig.

At the start of the ascent, Aimar rebuked Simpson for attacking up the hill, saying: “Don’t be an idiot. Stay on my wheel as I gather speed for the climb. Stay calm and limit the damage.” The French rider, who was fond of the Englishman, looked across to make sure the message had got through but he recalled: “He didn’t respond, he was like a zombie.”

There is a state cyclists refer to as the Red Zone, in which amphetamines overwhelm the body’s natural safeguards, and the race itself becomes all-consuming. It is possible that, through a lethal cocktail of drugs, exhaustion and heat, Simpson had entered such a state on his last climb.

He was in sixth or seventh, in pursuit of the peloton of leading riders who had the summit in sight, when he started to lose control of his bike. When he crashed, the team car raced over. Hall tried to reason with Simpson, saying “Come on Tom, your Tour is over” but the rider demanded to be put back on his bike. Team manager Taylor said: “If Tom wants to go on, he goes on.” In retrospect, this sounds foolhardy, even callous but, as Saunders wrote: “[Tom] was still in possession of all his faculties, he recognised people and spoke to them by name but, as he weaved across the road for the last time, and was held up by spectators, he had reached the end of his road.”

On film, the fact that he made it another 460m (500 yards), even with help, looks both miraculous and terrible – as if the last part of Simpson’s system that was still functioning was his competitive instinct. (Hence his exhortation, probably mainly to himself: “On, on, on.”) After that second crash, his fingers had to be prised from the handlebars and it took two helpers to do the same with his jaw. Opening it to give him mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. The medics also tried cardiac massage but everyone at the scene knew it was hopeless.

It took a while for the news to reach other riders. Lewis saw that his team-mate had come off his bike but had no idea how serious the crash was because Taylor waved him on, shouting: “Keep going, Tom’s ok, keep looking behind for him.” Lewis did exactly that: “All the way down the Ventoux towards Malaucene, I kept looking behind to see where Tom was. He never arrived and I didn’t know what had happened. I thought maybe he’d fallen and got injured.” Only back at the hotel, when his team-mate Hoban returned, did he learn the awful truth.

At breakfast the next morning Lewis and team-mate Arthur Metcalfe told Taylor they were quitting the Tour. They only changed their minds when the manager told them “Tom would want you to finish the race,” which was cruel, but also undeniably true.

The other riders were so shocked – remember, no one had died on the Tour for 32 years – that they only agreed to race the next stage to honour Simpson, assembling at the starting line the next morning in silence. The plan, suggested by Stablinski, was that the dead cyclist’s closest friend Vin Denson would win the stage in his memory. It didn’t quite work out that way. Hoban rode to victory, later claiming variously that he had expected the pack to catch up with him when he broke away and could not remember anything apart from finishing first.

There is a modest, pale grey marble memorial to Simpson on Ventoux. When Wiggins rode past it on his way to winning the Tour in 2012, he felt a strong spiritual connection to his hero. Five years later, he unveiled a new memorial in Haswell, Simpson’s birthplace. Mark Cavendish, who shares the record for most stage wins on the Tour de France with Merckx, also used to raise his helmet in salute, as did gifted Scottish cyclist David Millar, who was banned for drug abuse in 2004 (and is now a leading campaigner against doping).

In a foreword to a 2009 edition of Cycling Is My Life Miller wrote: “I hold his memory very close because he is a person I can relate to more than most. Tommy and I share many traits and have followed similar paths. I, like him, immersed myself completely in a world that was very foreign to me in the pursuit of a dream. As with Tommy, that dream became life-consuming; as with Tommy, it ended up with my doping. But I have survived where Tommy didn't.”

Simpson had raced himself into oblivion once before in Italy, losing consciousness as he slumped against a wall. As he recalled later: “I just wanted to die. I felt as if I was going and coming back. You don’t have to worry about dying because I died that day. I felt as if I’d gone and I was looking down on myself and then I brought myself back down. I’d been floating in a dream world, no more pain or suffering, it was a wonderful feeling.” On that stifling summer afternoon of July 13 1967, as he lay unconscious on a bed of stones near the summit of Mont Ventoux, Major Tom could not bring himself back down a second time. Having effectively ridden himself to death, Simpson’s pain and suffering were finally over, but the legend wasn’t.

Forty-five years later, on the 2012 Tour, as David Millar raced past the spot where his hero died, he threw his cap in the air in salute. By a remarkable coincidence, the spectator in the crowd who caught it was Simpson’s daughter Joanne. On the cap, Millar had written: “To Tommy, RIP.”